How Steve Swenson and Bob Menne Took on the Iron Dog

By Kim Kisner, Contributing Writer

At its core, the Iron Dog is more than a race — it’s a crucible of decision-making where every choice could mean the difference between glory and disaster. It’s life-or-death in motion. It’s also a teacher, a memory-maker, a bond-forger. For racers like Steve Swenson and Bob Menne, the Iron Dog isn’t just a test of skill and endurance — it’s a life experience that rewires you.

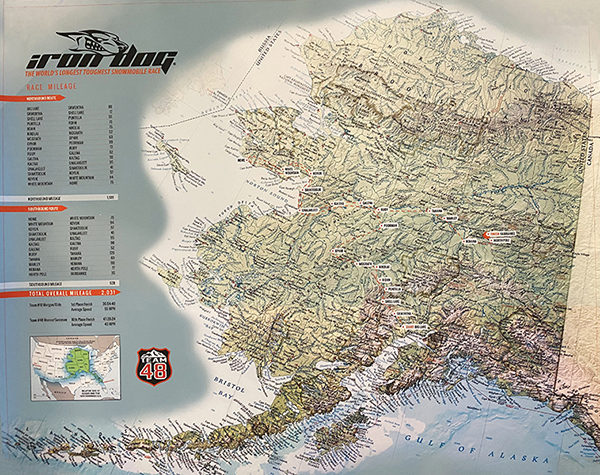

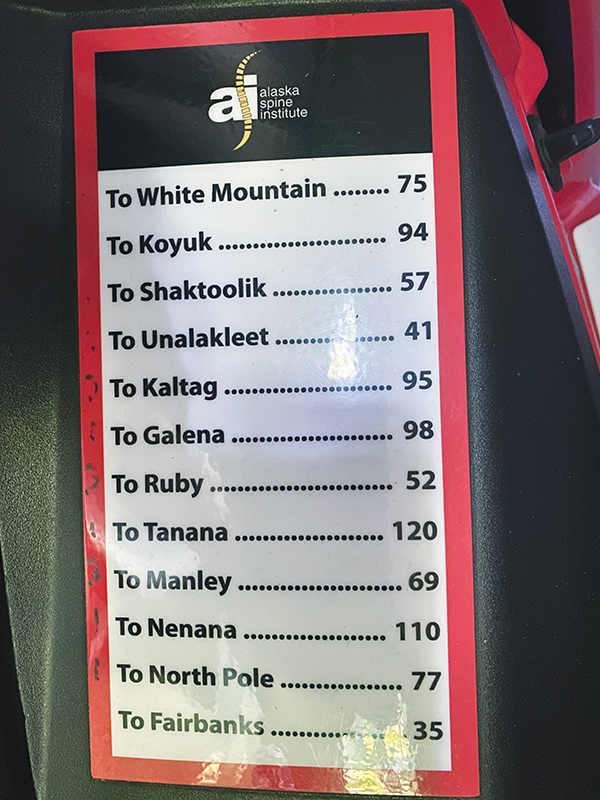

The Iron Dog is the world’s longest, toughest snowmobile race — a 2,500+ mile expedition across Alaska’s rugged, remote wilderness, launched in 1984 and now woven into the fabric of the state’s winter identity. It traverses tundra, mountains, frozen rivers, and sea ice in temperatures that routinely drop well below zero. For racers, it demands not only physical and mechanical endurance but also relentless focus and total trust in your teammate.

Because of the race’s magnitude — its danger, depth, and the unmatched community around it — we’re launching a six-part series spotlighting the people who’ve experienced it. Not just the pros and veterans, but the first-timers, the family connections, the dreamers, the rebuilders. The ones who have stories that stay with you.

This is the first installment: the story of Steve Swenson and Bob Menne, a pair of Minnesota racers who ran the Iron Dog together in 2018 — a journey that started with a last-minute flight to Alaska, a seat on a bush plane, and a son named Bobby.

Their story started not in Alaska, but in the stands — watching Bob’s son, Bobby, compete in the 2016 Iron Dog after being called in at the last minute to replace an injured racer. Bob and his family were watching from their home in Minnesota when, on day two, they couldn’t take it anymore. They booked a last-minute flight to Alaska. When they met up with Bobby during a layover in Nome, he told Bob, “You’ve got to fly in the parts plane.” That single flight — over the racecourse in a bush plane, following the riders below — gave Bob a glimpse of the vastness, the intensity, and the spirit of the Iron Dog. It stuck with him.

A year later, out riding back in Minnesota, Bob casually asked Steve Swenson — an experienced racer with a long history in off-road events, including a near-podium finish in the legendary I-500 cross-country snowmobile race — “Would you ever run the Iron Dog?” Without hesitation, Steve replied, “In a heartbeat.”And that’s how the plan began.

Gearing up for the Impossible

At ages 51 and 52, both experienced racers and Polaris veterans knew this wasn’t something they could enter lightly. They trained hard — physically, mentally, and mechanically. “We spent a year getting in shape,” said Bob. “You’ve got to be prepared — if you’re not, you crash. And when you crash out there, it’s not just a busted sled. It’s dangerous.”

They logged over 4,000 trail miles in brutal winter conditions back home. Steve recalled riding in temperatures 30 below zero, doing everything possible to mimic what Alaska would throw at them. “The faster you go, the more brutal it gets on your body and machine. So you learn — fast — how to balance speed, endurance, and mechanics.”

Steve put it bluntly: “In most races, you make decisions every few minutes. In Iron Dog, you’re making life-or-death decisions every few seconds — for 12 to 15 hours straight.”

Riding into the Unknown

In 2018, the two-man team lined up at the Pro Class starting line. “The first day was 300 miles,” said Bob. “It was brutal. Holes the size of bathtubs. Then you come around a corner and it’s open water — and you have to make a call, fast. I gave Steve a lot of credit — he was good at that.”

That dynamic was key. “When Steve made a decision, I followed,” said Bob. “That trust was everything.”

But even strong partnerships get tested. “Ten hours in, we’d already gotten in each other’s faces,” Steve said. “We were close friends. He was the owner of the company I worked for. It got intense.” By the end of nearly every leg, Steve would end up apologizing. “But that’s the race — it pushes everything. Your body. Your mind. Your relationships.”

Despite the intensity, they found moments of awe. “You ride for hours without seeing a manmade structure,” said Steve. “Just pure wilderness. Sometimes I’d want to stop and take it in, but you can’t.”

That sense of isolation is part of what makes the Iron Dog so powerful — and so dependent on community.

“There’s a lot of support on the Alaska side,” Steve said. “Vendors and manufacturers help make custom storage bags for each model year. They fabricate fuel tanks, build light brackets, and supply auxiliary gear. Everyone is more than willing to help.”

It’s not just about gear — it’s about being part of something bigger. “It’s a community,” he continued. “There’s real excitement when someone from the Lower 48 shows up to race. Cross-country racing is hard enough. Add the extreme cold, the remoteness — it’s a whole different level. But people step up. They want to see you succeed.”

The Miles That Change You

It wasn’t just the terrain. It was the mental grind. “We did over 1,100 miles in 32 hours with just two hours of rest,” Steve said. “Your brain gets foggy. You start to doubt. But you’ve got to stay sharp — you’re flying through blizzards, rivers, sea ice, and sheer cliffs.”

About 2.5 hours in, Steve had a moment. “I remember thinking, ‘What are we doing out here?’” he said. “But you realize — you can’t quit. It’s too hard to get out, logistically and mentally. The fastest, easiest, and most cost-effective way to get out of the situation is to keep going. To finish.”

At one point, they recalibrated their expectations. “We realized we weren’t running fast enough to podium, so we slowed down a bit,” Steve said. “And the funny thing is, sometimes slowing down actually makes you faster.”

And then there’s the emotional weight.

“Thirty miles from Nome, I started to get emotional under my helmet,” said Bob. “You realize — we’re going to make it.” But even that moment nearly derailed. Steve hit something, flew into the air, and came down hard. “I thought he was going to go end over end. But he held it together. And we just kept going.”

What Makes Iron Dog Different

Steve summed it up: “There are other races. But nothing like this. You’re riding through total darkness at 40 below zero, across ocean ice. There’s no warmup. No break. Just decision after decision, and no turning back.”

That constant decision-making takes its toll. “You’re maintaining focus, trying to go as fast as you can while preserving your equipment — all while you’re extremely tired and it’s the middle of the night,” Steve said. “The last day, the lack of sleep just crushes you.”

He recalled one moment that captured the contradiction of the race. “Say you come in at 5 p.m. and it’s dark. Then you leave again at 2 a.m., and it’s 40 below, and every part of you doesn’t want to go. But then you’re out there, turning onto the river, you hit your lights — and it’s like a warm blanket. You think, there’s no place I’d rather be than on my snowmobile in Alaska. It’s like living a dream… but it’s hard.”

Bob agreed: “You come upon a riverbank that’s a straight wall of snow. You don’t think. You grab a handful of throttle and hope. You’ve got to become one with your machine. It’s not just about knowing snowmobiling — it’s about knowing yourself.”

Advice for Future Racers

Their advice is consistent: Overprepare. “Look at it as a multi-year commitment,” said Steve. “Ride as much as possible. Ask people who’ve done it. Use their advice. And don’t overthink — buy a sled from a past team. Focus on what you need, not what you want.”

He added, “Ask for help from anyone who’s done it — there’s too much to learn the first time. Ride, ride, ride — you really can’t ride enough. Treat it like a multi-year endeavor, because that’s what it takes to truly be prepared.”

Bob agreed, “Don’t do this unless you’re really ready. Physically. Mentally. Emotionally. Because the Iron Dog will test every part of you.”

After All is Said and Done

As Steve put it, “Racing isn’t about who goes the fastest — it’s about who goes the slowest the least.” That mindset helped them succeed. “We kept our machines intact and made it in a respectable time,” he said. “It’s kind of rare for a new team running for the first time to even finish — especially being from Minnesota.”

After finishing the race, Bob had no interest in going again. “The timing was right, but it was a huge commitment,” he said. Still, it wasn’t the end of his Iron Dog journey. He and his family moved to Alaska, and in 2021, Bob became Executive Director of the Iron Dog — helping to steer the very race that had captured his heart.

Steve, however, still feels the pull. “If I could afford it, I’d do it every year,” he said. “It’s hard to explain. You go through something like that, and it changes you.”

And so the story of Bob and Steve is now part of Iron Dog lore — two racers from the Lower 48 who followed a dream, made it real, and walked away changed men. •